- Investment

- 科学论坛

-

Program

- Recruitment

- Center

News Message

Scientists Outfit Bees With Wireless Sensors

- by wittx 2019-04-24

Drones are growing in popularity for their ability to serve as a kind of eye in the sky. However, they can generally only last up to 30 minutes on a charge because of the limits of current battery technology.

Now, a research team at the University of Washington has found a way to make bumblebees act like tiny drones. The group has developed a platform for sensing, computing, and wireless communication devices that’s small enough to piggyback on the insects.

"We wanted to leverage nature's best flying machines," says Shyam Gollakota, a computer scientist at the University of Washington, who led the research. "Insects can feed themselves—we don't need to keep recharging their batteries. Fats and sugars can store much more energy for their weight than batteries."

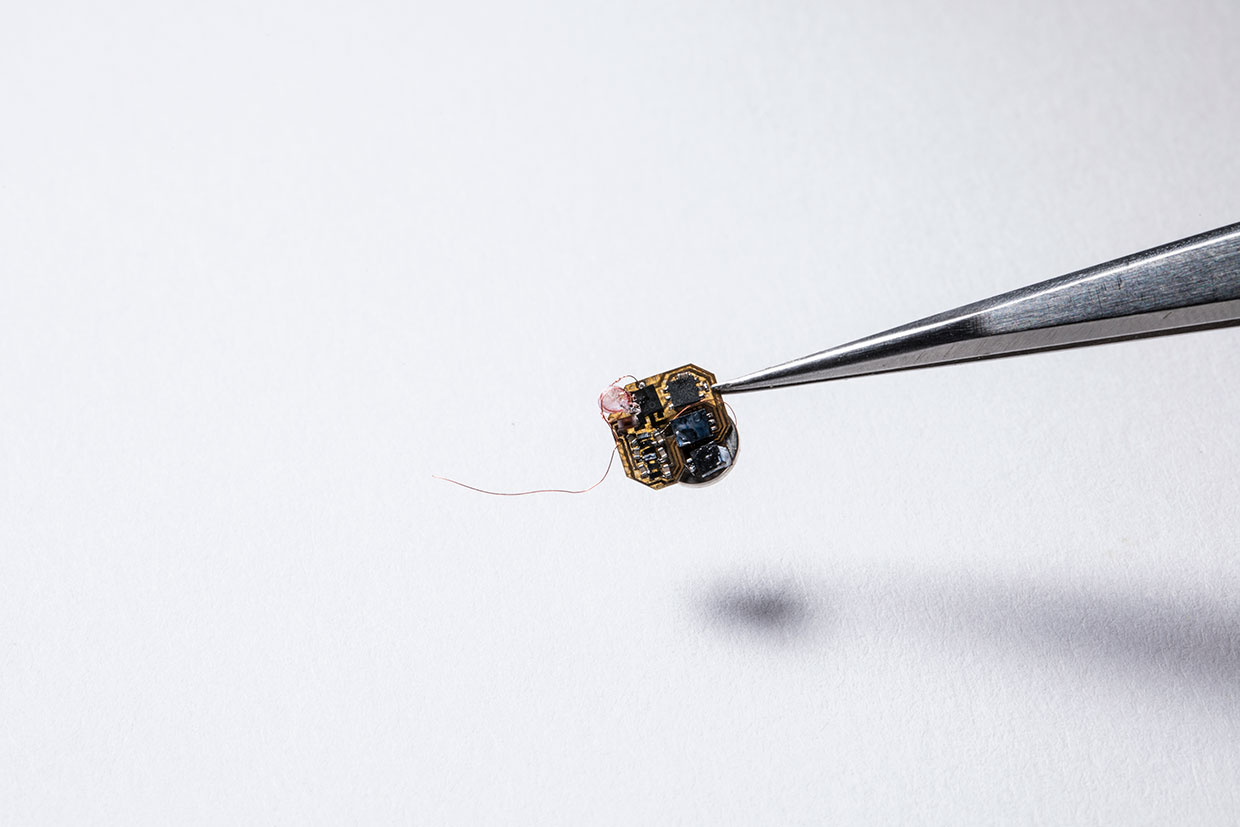

The scientists experimented with three species of bumblebees and found that healthy worker bees could fly and hover while carrying up to roughly 105 milligrams. Knowing this, the researchers developed an electronic platform that weighs only 102 milligrams and measures just 6.1 by 6.4 millimeters in size. It includes a 70-milligram rechargeable lithium-ion battery that can last up to seven hours, as well as a microcontroller, antenna, and sensors that could analyze humidity, temperature, and light intensity once every four seconds. Then, the research team glued these platforms onto the backs of bees. "All the electronics we used were off-the-shelf components," Gollakota says.

Photo: Mark Stone/University of Washington To use as little electricity as possible, the design eliminates many conventional radio components. Instead, it communicates by modifying radio signals that scatter off it, wirelessly offloading data at rates of roughly 1,000 bits per second after the bees return to their hives.

The researchers noted they currently have no way of controlling the movements of the bees. Still, they could pinpoint the insects’ positions. Instead of using a power-hungry GPS device, their design relies on special radio transmitters placed around the area in which the bees are expected to fly. These transmitters serve as beacons, and keep track of the bees’ locations as long as the bees stay within 80 meters of these beacons. "We can create maps from the data the bees' sensors collect," Gollakota says.

The scientists noted they could wirelessly recharge the battery at the hive within six hours. They also suggest that a solar cell might one day replace the battery in the design.

Potential applications for what the researchers call "living Internet of Thingsplatforms" might include smart farming to measure plant health. For example, moisture and humidity sensors could assist with precision irrigation, and temperature sensors can detect whether growing conditions are optimal for specific crops. Whereas "drones can't really fly between plants, bees can fly pretty much wherever they want to get more fine-grained information than drones," Gollakota says.

Sensors placed on bees might also shed light on their biology. This could yield insights into why bee populations are crashing, says co-lead author Vikram Iyer, a computer engineer and electrical engineer at the University of Washington.

In the future, the researchers might equip the bees with cameras, or with sensors that can measure electrical signals from the bees’ brains "to get a sense of how we might one day control their motions," Gollakota says.

The scientists detailed their findings on 11 December at the MobiComconference in New Delhi.

Share Http URL: http://www.wittx.cn/get_news_message.do?new_id=187

Best Last Month

Information industry by wittx

Information industry by wittx

Information industry by wittxInstitute for Theoretical Physics G¨ oteborg University and Chalmers University of Technology G¨ ote

Information industry by wittx

Information industry by wittx

Information industry by wittx

Information industry by wittx

Information industry by wittx

Information industry by wittx

.jpg)

Information industry by wittx